|

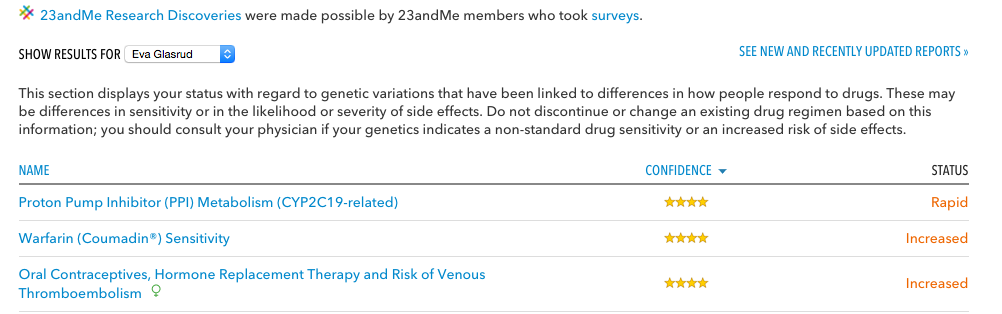

The best thing about running Paved With Verbs is how many engaging young people I get to work with every day. For example, last week, I met with a student who was writing his “Why do you want to go to Purdue” essay. We talked about his interests – he loves technology, but he wants to be a doctor. Hearing this, I told him to check out the Purdue Research Park. “You’d be a perfect candidate,” I told him, “Because medical breakthroughs aren’t happening in the field of medicine anymore. If you want to disrupt medicine, you need to take an interdisciplinary and collaborative approach. You’ll need to work with chemists, psychologists, engineers, doctors, and computer scientists.” And then I went on a long tangent about the pioneering new field of phamacogenetics. In the digital age, we’ve come far from the days when pharmacology and genetics were two separate fields. Traditionally, pharmacology research involved medicine. Not just what and how much, but also how drugs interact with the body, where in your body the drugs are broken down into medicinal compounds, how long they stay in the body, how they’re excreted, and how they should be administered. Of course, these scientists considered things like gender, weight, age and height in their studies. But beyond that, they didn’t really consider how, genetically, your liver might be different from mine. Genetically, I might have more of a certain kind of enzyme than you do. And that might have serious implications for how my body responds to the same medications as yours. For example, say we’ve had our wisdom teeth removed, and have each been prescribed codeine. We’re both supposed to take one pill every four hours. Codeine alone does nothing to relieve pain – only when it hits the liver, where the enzyme CYP2D6 converts it to morphine, is it effective. But! Due to natural genetic differences, some people produce too much or too little of the enzyme. When you produce too much CYP2D6, more codeine is converted to morphine – and faster. This could mean you have “pleasant” side effects... or you might have unpleasant ones like constipation and excessive sedation. It also means that you will likely be in pain again before you’re supposed to take your next dose, because you were supposed to metabolize the first pill over four hours, not one. Meanwhile, when you produce too little CYP2D6, you take the codeine… and nothing really happens. The liver doesn’t convert enough of it to morphine, and you have mild relief at best. So say I produce less CYP2D6 than average, and I spend the week after my surgery in pain – by the time I get to talk to my doctor and pick up a new prescription, my pain might already be subsiding. Meanwhile, you’ve basically spent the week getting high every hour, and then taking more pills because now you’re in pain again… and this could escalate quickly. Pharmacogenetics could tell us a lot about addictions. Another classic example of the importance of pharmacogenetics is warfarin. Warfarin is a blood thinner/anticoagulant that is often prescribed after a stroke. It’s extremely effective, reducing your chances of another stroke by 50% compared to aspirin and 70% compared to no treatment. However, 2-10% of patients experience a life-threatening bleed in their first year of taking warfarin. Not to mention those who have additional strokes in spite of the medication. The reason for this is that people’s response to warfarin varies dramatically due to genetics… and the best technology we’re using right now to determine the proper dosage is trial and error. We prescribe patients the average dose for someone of their gender and weight, and then we test their blood. If it’s dangerously thin (meaning you could have a serious bleed) at the follow-up appointment, they reduce your dose. If it’s dangerously thick (meaning you could have another stroke), they increase it. Then you go back every 1-3 weeks to get your dose adjusted again. According to the US Institute of Medicine, only 50-70% of patients on warfarin are receiving the correct dose. Yet two genes are known to be involved in warfarin processing, and there is convincing evidence that pharmacogenetics could help solve this problem. My 23andMe results say that I have an increased sensitivity to warfarin – as well as a “substantially increased risk of developing venous thromboembolism… if taking estrogen-containing contraceptive.” (One of many reasons I would never take birth control pills.) This information could help me make important medical decisions someday – you know, under the guidance of my doctor. Of course, 23andMe did just weather its first FDA-regulatory storm. But nevertheless, it's clear that the future of medicine… doesn’t just lie in medicine. It’s all about collaboration. In fact, some colleges, including UT Austin, have a supplemental essay specifically asking applicants to write about a time when they collaborated. Describe a setting in which you have collaborated or interacted with people whose experiences and/or beliefs differ from yours. Address your initial feelings and how those feelings were or were not changed by this experience. Read more > Schools like Stanford routinely boast about how easy it is to collaborate on their campus -- especially with Bio-X, Stanford's pioneering interdisciplinary biosciences institute. (Want to get involved as an undergrad? Take advantage of the Bio-X Summer Research Program!) When my grandpa went to college, he majored in “Engineering,” because that was something you could major in back then. Just straight-up engineering. Not civil, mechanical, electrical, chemical or biomechanical. Today, many schools have multiple majors within their Mechanical Engineering Department. In the information age, it is impossible to be an expert at everything. Collaboration isn’t a fuzzy, feel-good buzzword – it’s the way science and innovation are done now. And if you can’t collaborate, there is a very definite limit to what you will be able to accomplish. So take your group projects seriously. Explain your ideas to students and teachers with different interests from yours – and pay attention when they share their input. When developing an idea, don’t just think about what you know – think about what you don’t know, and how a partner with expertise in that area could compliment or accelerate your work. Because, trust me: colleges will be just as (if not more) impressed by your story about a successful collaboration than one about something you did “all by yourself.”

1 Comment

nks for sharing the article, and more importantly, your personal experience of mindfully using our emotions as data about our inner state and knowing when it’s better to de-escalate by taking a time out are great tools. Appreciate you reading and sharing your story since I can certainly relate and I think others can to

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorEva Glasrud completed her B.A. and M.A. at Stanford. She is now a college counselor and life coach for gifted youth. Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed